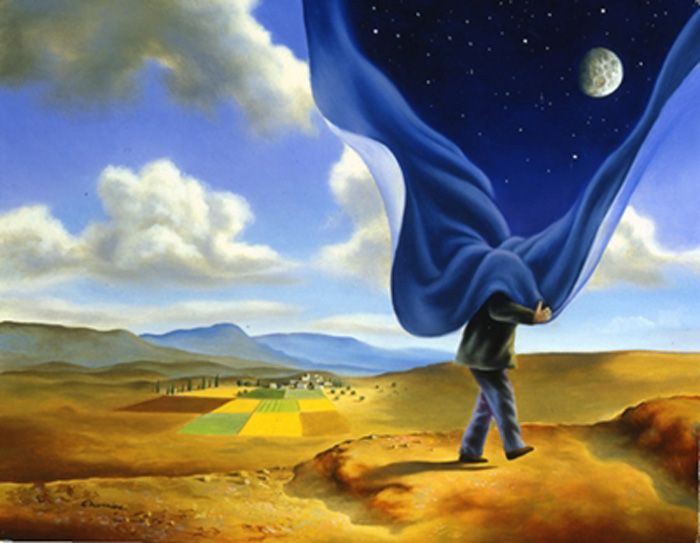

"Almost Time" by Samy Charnine

Our experiences at Takiwasi and completely reestablishing our life from the USA into Peru this year, has led us into a deep learning process, which in fact has gone deep enough to lead us back to our roots! We are living in Tarapoto at this time, where we are exploring prayer from our childhood, self-discipline, occasional visits to the ceremonial space and a new found internalization on how one has to become more responsible as one asks for and receives the gifts of knowledge. It has been a very challenging year, and yet when we zoom out to the border perspective, we find that this is exactly what we've needed.

Dr. Jacques Mabit's short lectures and the article below by Felix de Rosen are very pertinent and important for the current state of affairs surrounding curanderismo (the science and art of healing with plant medicines).

Dr. Jacques Mabit's short lectures and the article below by Felix de Rosen are very pertinent and important for the current state of affairs surrounding curanderismo (the science and art of healing with plant medicines).

| | | |

The Joys and Pains of Visionary Medicine: Why the Ceremony of Life Comes Before the Ayahuasca Ceremony

by Felix de rosen

The German poet Goethe never attended an ayahuasca ceremony. Nonetheless, his words contain useful advice for those wishing to explore visionary realms. In his poem The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, Goethe describes a young apprentice who must clean his master’s workshop while the latter is away. The apprentice doesn’t want to do this by hand, so he uses one of his master’s spells to enchant a broom to clean for him.

Voila!

The broom begins fetching water and scrubbing the floor. Soon the floor is flooded as the apprentice realizes he doesn’t know how to end the spell. He tries splitting the broom in two with an axe, but each half becomes a whole new broom and the chaos doubles as torrents of water crash their way through the workshop. When all seems lost, the sorcerer returns and breaks the spell, sternly warning that the spirits should only be called by those who understand them.

What is Goethe telling us? The apprentice knows how to open the floodgates of spirit, but is overwhelmed when the spirit takes on a life of its own. The apprentice is still learning the way. Unfamiliar with spirits, he invokes them to do something he should be doing himself: cleaning the workshop.

Notice the role of water in the poem. Normally a source of life and purification, here water plays the role of destroyer. The spirit of healing becomes an agent of chaos. The apprentice doesn’t realize the power of the spirits he has called and the channel he opens literally floods him. Goethe’s lesson is simple: the master’s magic is not a casual affair. It is sacred work, direct communion with the very fabric of reality.

Working with plant medicines like ayahuasca, we in the West are much like the assistant in Goethe’s poem. Although there was a tradition of psychotropic plants in Europe, much of it has been lost, leaving foreign indigenous traditions as the best models for us to learn from. These traditions, passed on through master-student lineage, contain countless generations of accumulated experience, which has allowed them to develop sophisticated evidence-based protocols for working with these plants.

Compare this with the West, where ayahuasca was unheard of less than 50 years ago. Today, it is a household name amongst alternative health seekers, the spiritually inclined, and curious psychonauts. If we want to explore plant medicine (and remember, there are other tools available), then we must learn from indigenous visionary traditions in addition to practicing common sense.

Voila!

The broom begins fetching water and scrubbing the floor. Soon the floor is flooded as the apprentice realizes he doesn’t know how to end the spell. He tries splitting the broom in two with an axe, but each half becomes a whole new broom and the chaos doubles as torrents of water crash their way through the workshop. When all seems lost, the sorcerer returns and breaks the spell, sternly warning that the spirits should only be called by those who understand them.

What is Goethe telling us? The apprentice knows how to open the floodgates of spirit, but is overwhelmed when the spirit takes on a life of its own. The apprentice is still learning the way. Unfamiliar with spirits, he invokes them to do something he should be doing himself: cleaning the workshop.

Notice the role of water in the poem. Normally a source of life and purification, here water plays the role of destroyer. The spirit of healing becomes an agent of chaos. The apprentice doesn’t realize the power of the spirits he has called and the channel he opens literally floods him. Goethe’s lesson is simple: the master’s magic is not a casual affair. It is sacred work, direct communion with the very fabric of reality.

Working with plant medicines like ayahuasca, we in the West are much like the assistant in Goethe’s poem. Although there was a tradition of psychotropic plants in Europe, much of it has been lost, leaving foreign indigenous traditions as the best models for us to learn from. These traditions, passed on through master-student lineage, contain countless generations of accumulated experience, which has allowed them to develop sophisticated evidence-based protocols for working with these plants.

Compare this with the West, where ayahuasca was unheard of less than 50 years ago. Today, it is a household name amongst alternative health seekers, the spiritually inclined, and curious psychonauts. If we want to explore plant medicine (and remember, there are other tools available), then we must learn from indigenous visionary traditions in addition to practicing common sense.